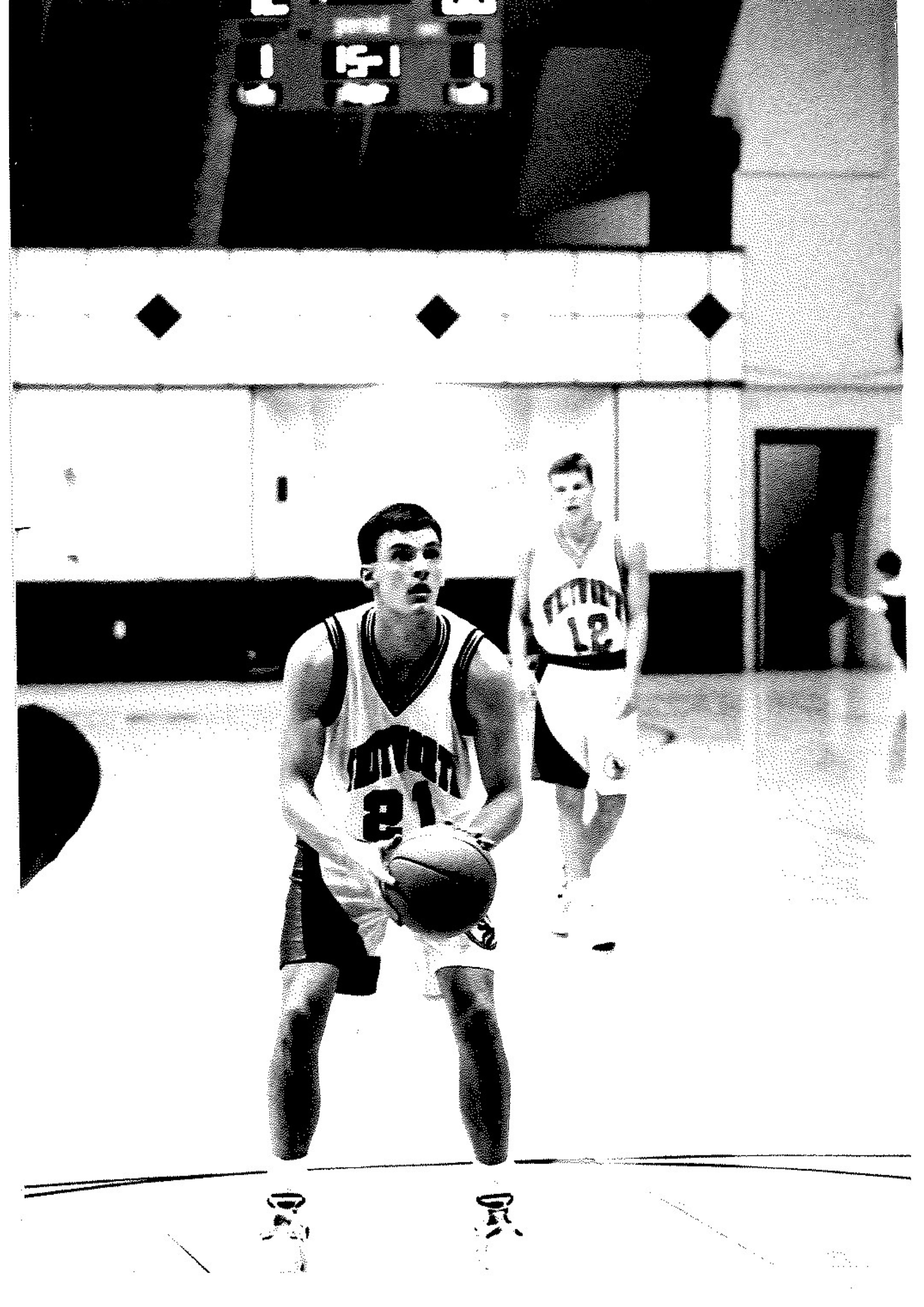

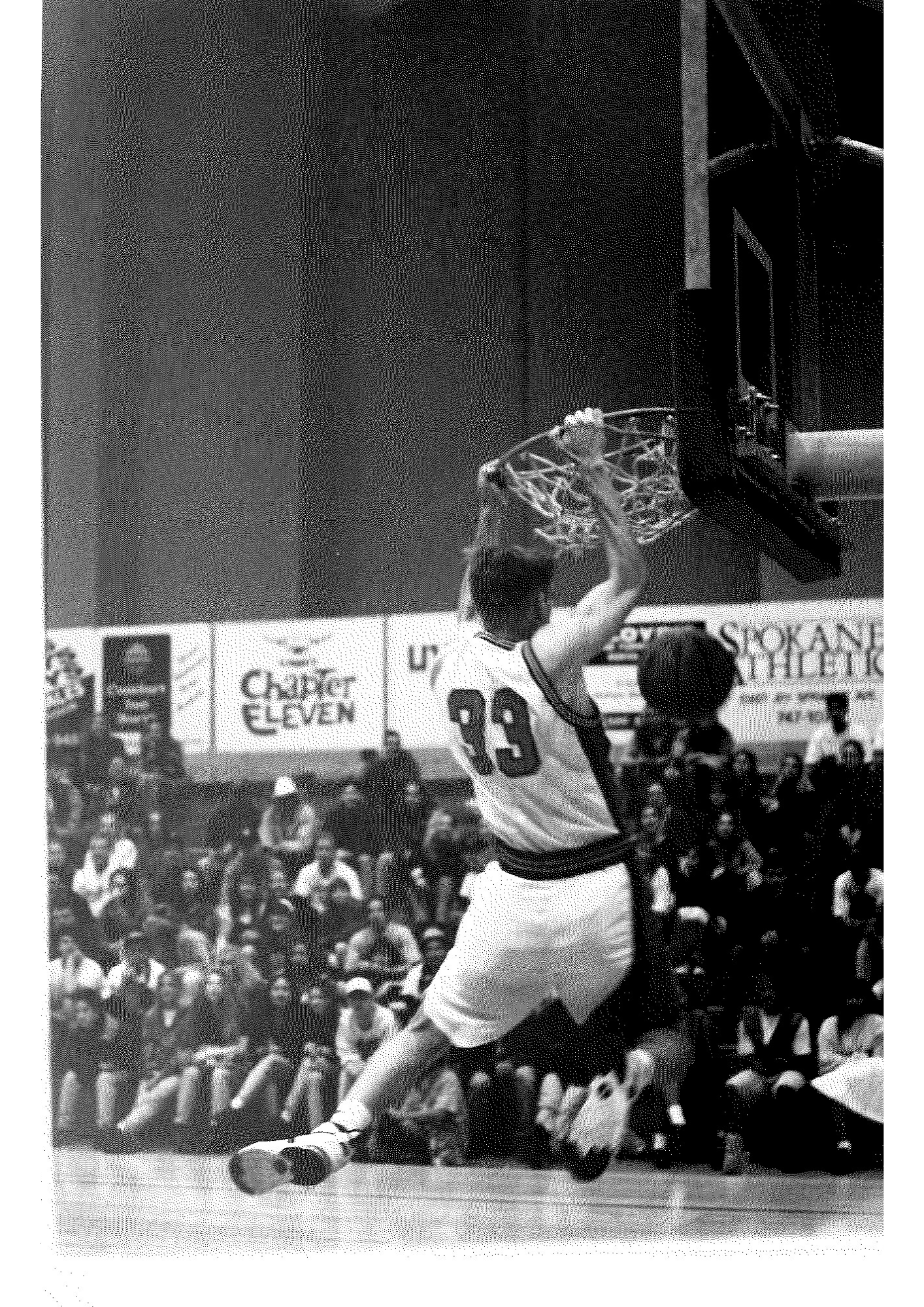

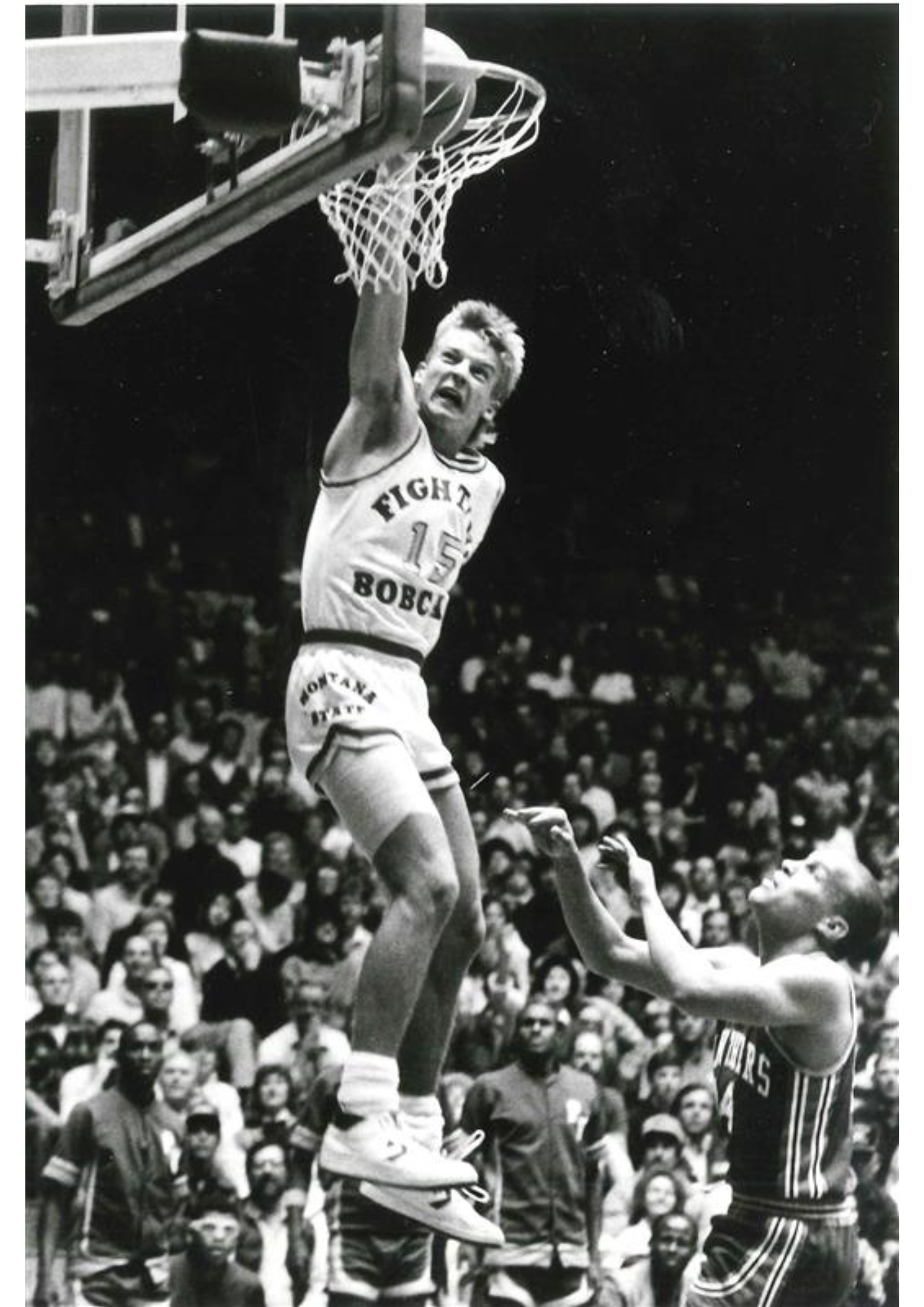

Whitworth Mens 1996 Basketball - Hooptown USA - HALL of Fame 2022

They didn’t get the winning shot to go, or the whistle to blow. No spoiler alert is necessary to report, nearly three decades later, that the national championship eluded the Whitworth Pirates of 1996.

They didn’t get the winning shot to go, or the whistle to blow. No spoiler alert is necessary to report, nearly three decades later, that the national championship eluded the Whitworth Pirates of 1996.

Anyway, it can be argued they did something grander.They got the school president to shut down the school. They launched a last-minute caravan -- six buses, countless cars -- that covered 400 miles to reach the title game. And mostly they revealed Spokane's nascent appetite for a basketball cause and diving cannonball-style into those delirious moments -- not that the players recognized it as it happening.

"I was just playing and feeding off the electricity," said Nate Dunham, a senior who had experience with a small school doing big things growing up in little Almira. "No way I thought people would still think of it as special in the story of Spokane basketball."

But the Pirates of '96 were special, as acknowledged by their induction into the Hooptown Hall of Fame.

The basketball madness of March is a different animal for the Whitworths of America, in a universe not ruled by the office bracket pool and "One Shining Moment." The Pirates were still members of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics in the mid-1990s, winning their way into the organization's raucous Division II tournament -- 32 teams, six days, one steamy fieldhouse in Nampa, Idaho.

Of course, before that crescendo were many mezzo moments, one dating back a decade.

Warren Friedrichs came to Whitworth in 1985 as the school's seventh head basketball coach in just 11 years, a steadying hand whose clerical demeanor -- he had once studied to be a minister -- masked a fierce competitiveness. He'd restored dignity to the basketball program and got the 1991 team to nationals, falling in the first round.

The heart of the next wave was Dunham, a State B champ at Almira/Coulee-Hartline who had won over Friedrichs' admitted bias toward recruiting from larger high schools by "making every right play." The other starter inside, Jeff Arkills, might take only four shots a game, but the coach retooled his offense the year before just to accommodate him in the lineup ("He'd take a charge in Hoopfest on concrete," Friedrichs marveled).